Venturing on the frontier: founders as capital architects

AI has both concentrated conviction and driven disorientation in venture capital. Every VC wants exposure to the latest AI winner, but it’s hard to stomach paying 200x ARR to fund yet another AI-powered platform for legal or customer support. Some investors are paying up. Others are searching for the AI-native plays that are less crowded. But many are blindly sprinting towards whatever does not look like the last consensus trade.

This time, that means venture dollars are rushing into categories with novel risk, and bespoke, complex financing needs:

- AI rollups: Acquire distribution in fragmented markets, integrate AI across the portfolio, harvest margin expansion. Think: rolling up dental practices or accounting firms and deploying AI back-office automation.

- Deep tech & hard science: Fusion, novel materials, drug discovery platforms. The bet: AI will compress the innovation cycle in physics, chemistry, and biology.

- Vertically-integrated, software-first infrastructure: Software is the wrapper; the asset is the business. Think companies like Mariana Minerals (which looks like “mining tech” until you realize it’s actually just…a mine.)

- Compute, power & energy supply: Data centers, nuclear reactors, battery storage. The classic "picks and shovels" play for the AI boom.

- AI-native services / agentic BPO: Traditional service businesses (accounting, compliance, back-office) repackaged with AI agents and sold as software margins.

- Distressed tech assets: Recaps, carve-outs, IP auctions. Buying yesterday's failed bets at a discount and re-positioning them for today's narrative.

There are real opportunities in all six categories. (And we’ve invested in some!). But the reason this moment is dangerous is that many venture investors are entering these markets with the wrong mental model.

For 15 years, software venture capital operated under a single implicit rule: “If the founder is great and the product works, there will always be capital available.”

That rule worked because software was capital-light, margins were high, distribution was the bottleneck, and every round of capital came from a fund that was just a larger version of the last one.

This approach breaks down on the frontier, because in these categories, the next check isn't necessarily a VC check.

It might come from:

- An infrastructure lender evaluating debt service coverage ratios

- A sovereign wealth fund doing project finance

- A government loan program with regulatory strings attached

- An industrial offtaker who wants volume guarantees

- A specialty insurer who won't touch the risk profile

These financiers don't care about NRR, PLG, CAC or that sexy launch video you just posted on X. They care about: offtake certainty, EPC risk, DSCR ratios, feedstock pricing, regulatory approvals and countless other details.

All of this reveals an uncomfortable truth: VCs may be the most networked financiers in the world, but only with each other. They know every Series A partner, every multi-stage fund, every angel and scout. But they don't know the infrastructure debt syndicate in Houston, the ECA lenders in Europe, or the commodity traders who might provide prepayment financing.

Which means many VCs are now underwriting companies where financing is the real risk, while having almost no ability to evaluate whether that financing will actually materialize.

The new model: founders as capital architects

To win in these new frontier markets, founders will often need to devote as much attention to designing their capital stack as they do to product, engineering, and go-to-market. Their competitive advantage will be building products in forms that unlock cheaper, earlier, or more patient capital.

Two case studies:

Case Study: Venture Global LNG

Venture Global didn't invent liquid natural gas technology. They redesigned the export terminal itself.

Traditional LNG facilities are massive, bespoke construction projects built on-site over 5-7 years. Venture Global designed modular liquefaction trains manufactured in factories, then shipped and assembled on location.

The result: Construction time compressed to ~3 years, execution risk dropped significantly, and cost predictability improved. That architectural choice unlocked $13+ billion in project financing at rates traditional LNG couldn't access. Banks could suddenly underwrite it like infrastructure, not like a moonshot. Today the company generates $5 billion in annual revenue, carries a $37 billion market cap, and is on track to become the largest LNG exporter in the US.

The technology mattered. The financing architecture mattered more.

As an aside, we're seeing the same pattern play out in nuclear with companies like Blue Energy (an Angular portfolio company), which is applying modular, off-site manufacturing to small reactors and transforming nuclear from an unfinanceable megaproject into something that looks more like deployable infrastructure.

Case Study: Solugen

Solugen didn’t invent synthetic biology, but it redesigned bio-manufacturing to qualify for government infrastructure loans.

Traditional biotech facilities can't access DOE loan guarantees because they're considered R&D risk, not infrastructure. Solugen designed their modular "Bioforge" facilities to meet the technical, environmental, and commercial standards that government project finance requires: standardized components, predictable CapEx/OpEx, contracted offtake agreements, and co-location with feedstock suppliers (their Minnesota facility connects directly to an ADM corn processing plant via pipeline).

The result: In 2024, Solugen secured a $213.6 million DOE loan guarantee, which is the largest U.S. government investment in biomanufacturing in decades. That's not venture capital. It's infrastructure-grade financing at government rates, unlocked because they architected the business to look like a utility-scale project rather than a lab experiment.

The technology mattered. But the insight that biotech could be redesigned to qualify for infrastructure finance…that was the breakthrough.

In both cases, novel technology was crucial in unlocking the opportunity, but it wasn’t enough. The insight that allowed both Venture Global LNG and Solugen to win was that the business could be architected to unlock non-venture financing. That was the true breakthrough. This is an inversion of the classic relationships between technology and finance. In traditional VC, finance enables technology. On the frontier? Sometimes technology enables financing.

A framework for building on the frontier

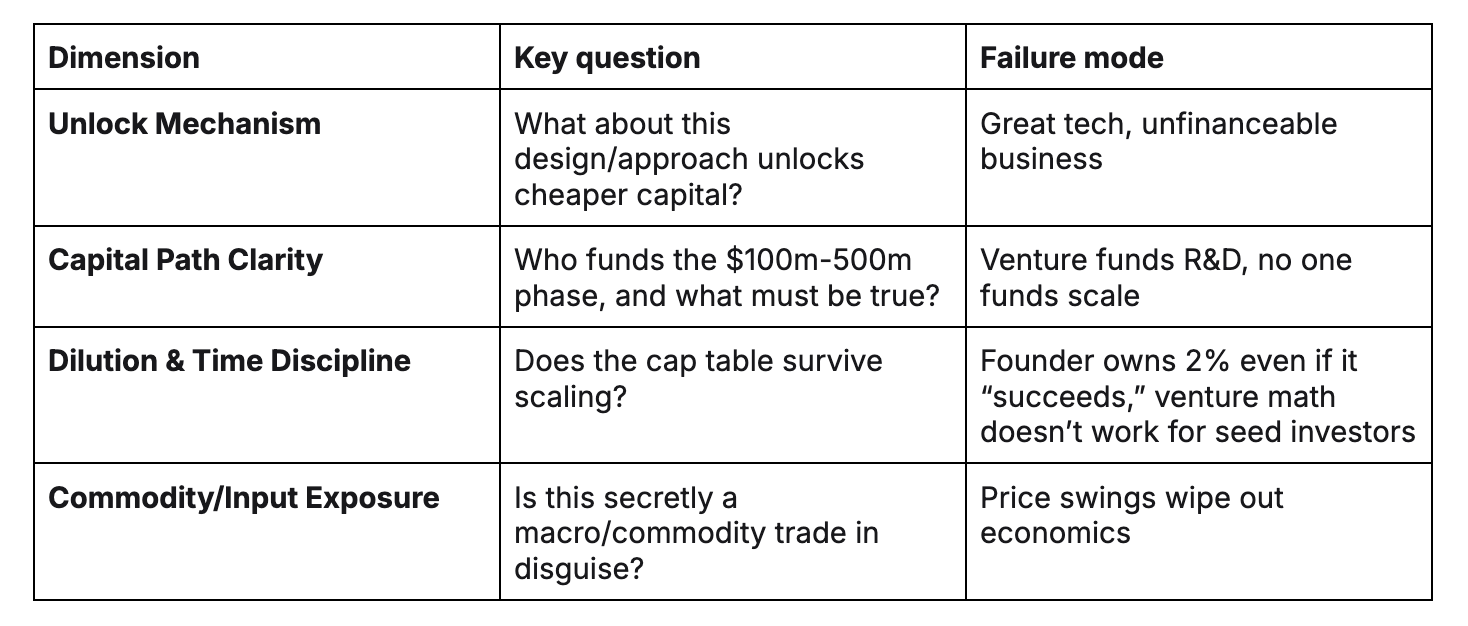

To succeed in these markets, founders and VCs need to evaluate companies along at least four dimensions:

This framework is hard-earned. Every dimension represents a failure mode we've either seen firsthand or barely avoided. The companies that survive the frontier aren't the ones with the best technology, they're the ones where the founder understood, from day one, that financing was a first-class design problem, not an afterthought.

Here’s another way to frame it. Venture capital is normally thought of as funding technical breakthroughs that unlock growth. Venture capital on the frontier is about funding capital coordination problems disguised as technology companies.

The firms that understand the game is no longer just "back great founders with great products," but "back founders who can architect financeable businesses" will dominate the next decade.

At Angular, we're specifically looking for founders who see the world this way. Founders who don't just pitch the technology, but who can articulate the capital path. Who understand that the innovation isn't just in what you build, but in how you make it financeable.

If you're building in any of these frontier categories and you think about financing this way, we want to talk to you.